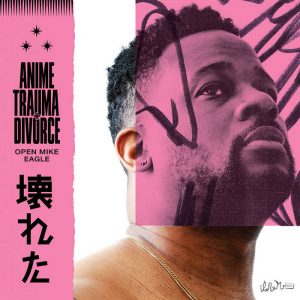

KCSB x OPEN MIKE EAGLE INTERVIEW

Open Mike Eagle’s new project is quite literally about Anime, Trauma and Divorce. It’s a nonchalant trip down the rabbit hole of Michael W. Eagle II’s spiraling imagination as he works through a divorce, the trauma that proceeds & ensues, and it’s all told through comical lyrics and his signature anime references. Although you can tell that Open Mike’s getting older, his latest album fits around his hands like snug mittens. Yes, Anime, Trauma and Divorce covers all of the bases of a classic Open Mike Eagle album, from his mixture of sung-rap & introspective spoken word to his clever one-liners & pop-culture references, but it also gives him quite a bit of room to explore sounds that he hasn’t dipped into before.

Image courtesy of Open Mike Eagle

Anime, Trauma and Divorce is distinct in how it sounds more like LA than any of his previous albums. This could be due to a number of reasons, from discussing themes that are inherently more social (e.g., relationships, daily life), to his new collaborations on the project, working with Los Angeles-based artist Kari Faux and his incorporation of minimal, legato production that embodies the city’s breeziness. It’s light, it’s digestible, but the lyrics still weigh heavy on Open Mike’s conscience. He’s clearly more despondent and cynical than ever before, but you can have faith that our narrator will be able to trudge through the emotional wasteland that he’s been forced into, in the same manner as a protagonist in an anime—all thanks to an undisclosed Black Mirror episode. Open Mike Eagle is showing us the chinks in his armor, and all we can do is sit back and listen as he ardently vents, makes jokes, and ultimately attempts to heal himself along the way.

When I speak with Open Mike Eagle, we discuss what it’s like to grow up in Chicago, his mental state when he was working on his new album, Anime, Trauma and Divorce, and his DIY work ethic as an independent artist in the streaming era. At 40 years old, Open Mike has notably been able to forge his own lane in hip-hop, the subgenre of “Art Rap” to be exact, and he’s still pushing it towards a new, ever-changing direction. Meet the man of many names—rapper, comedian, wizardry talk show host, Lord Bravery himself—Open Mike Eagle.

Yousef: Looking back, what was it like to come of age in Chicago?

Open Mike Eagle: I came of age at a really particular time, the mid-90s into the late-90s. When I think back about that time, it was a big time to transition. I’m of the generation where we saw the Internet happen. We were in high school as the world was completely changing. I think neighborhoods started changing a lot then too. Gentrification felt like it got ramped up around that time. When I go back to the spots that I used to hang out at in Chicago, it’s really different now; a lot of new development, a lot of erasure of old places. It feels like I grew up in this really particular time capsule, which I guess everybody kind of feels like too, but Chicago has really changed a lot from when I grew up there.

Yousef: You touch on this on Brick Body Kids Still Daydream, but how did it feel when the projects you grew up in were torn down?

Open Mike: I didn’t necessarily grow up in them. My aunt’s family lived there, and the building that I lived in wasn’t in the projects, but it was a mile away at best, so we were there a lot and spending a lot of time in those buildings. They didn’t get demolished until I was in college, and I was so deep in my personal life in college that I didn’t really know it, so it took me a few years to look back like, “Wait a minute, those buildings got torn down.” Then, I started looking into what that area is like now, because I couldn’t imagine there being fancy, new condos in that area. It was always so tucked away, and it seemed kind of sectioned off from everything. Eventually, I went to go see it, and that’s when it really hit me. There’s nothing there. They tore those buildings down just to tear them down, just because the people had decided that their existence was a bad idea. There was no redevelopment, just a blank empty field, and that to me was the worst part—the erasure just for the sake of erasure. There was a lot of culture there. As dangerous as those places were, and as underserved as they were, that lets all sorts of calamity and chaos, there were still 30,000 people in those buildings. I think it was 17 buildings, or something like that, maybe 12, but there were a lot of people in this condensed area. There was this culture, 4/5 generations of that just got scattered to the wind.

Yousef: Just nowhere to go after that.

Open Mike: They put a lot of people in subsidized housing all around the city, but that created problems because this is low-income, high crime [if you use those sorts of labels], but it was self-contained. Now, you’re mixing people into other neighborhoods where there’s other gangs and things that they have to mix in with now. I think it caused a lot of chaos to spread throughout the city, the way they handled it. They weren’t paying attention to stuff like that. Then, you have 10,000 people that they just lost, that are just not in the system anymore. They don’t know what happened to those people. It just wasn’t well handled.

Yousef: Before you were rapping full-time, you also worked for AmeriCorps and at a non-profit halfway house. How did that impact how you’ve approached your career as a rapper?

Open Mike: I don’t know how much it’s approached my career; I think it’s approached how I am as a person, in terms of knowing how important it is to be able to articulate whatever point it is that I’m trying to make. I think it gave me a lot of patience—I was dealing with a lot of kids, and a lot of kids that had been failed by the system already, and kids that had come from really awful circumstances that are just trying to have a life. It gave me a lot of perspective when it came to what the state of the world is. I think that that carried over into my music. I think the effects were largely personal for me, psychologically, and in terms of how I deal with people.

Yousef: Being from Chicago, did you ever feel compelled to test the waters in any of the city’s other subgenres, from the drill scene to gospel rap to conscious hip-hop, even though your music is somewhat conscious itself?

Open Mike: I definitely come from that lineage of conscious—Common, back when he was known as Common Sense, was a local legend to us because he grew up blocks away from where we were, and he was making it. He was making music with some of our heroes. I think the subsect of rap that I came up in was really looking at him as one of the leaders, and that subsect had a lot of “conscious” energy to it, and I think we gravitated towards that label. A lot of that other stuff, when you look at gospel rap and drill, a lot of that stuff happened after I left the city. The beginnings of a lot of that happened when I was in college and when I moved to LA already. Drill, I think, has roots in gangsta rap from the West Side, because the West Side had always taken more of a cue from West Coast rap; it was always a little darker and always a little more dangerous and gangster, and I think that’s what developed into drill. The gospel rap thing, for me, really came out of nowhere. Once it happened, I could see—there’s such a rich lineage. If you look backwards towards the migration of black people in America, all the black people in Chicago are from the South. There’s a lot of that black, Gospel, Baptist church tradition that came with those black people to the city. There’s always going to be a little bit of that flavor in the folks of Chicago. I do think that it makes sense, I just didn’t see it coming.

Yousef: When you did move to LA, how do you think your sound changed, artistically?

Open Mike: I got down with a collective called Project Blowed out here in LA. The people who are the most known out of that are probably Aceyalone, Abstract Rude, Freestyle Fellowship, and they’re loosely connected to people like MURS and The Pharcyde. What they’re known for is exploring the different styles of rap, and it’s really important, if you’re down with that collective, to master a bunch of different styles. I came from Chicago where there was one style that I mastered, a punchline, one-liner, and trying to be most effective that way. When I came out here to LA, a lot of the training, or what I became steeped in, with Project Blowed was exploring the different styles and learning how important it was to be able to come at the mic a bunch of different ways, to have a bunch of different approaches in my toolbelt. I think that’s affected a lot of the way that I would write rhymes going forward.

Yousef: Was it through Project Blowed that you met Dumbfoundead and Psychosiz, or how exactly did the three of you come together?

Open Mike: Yup, absolutely. The thing about the Project Blowed is that it had been around for 25 years. What that meant was that there was always a new generation of people coming to the Blowed; those people would clique up and make groups and then try to make a career of it. The generation that I started coming with, Psychosiz and Dumbfoundead and Sahtyre and Lyraflip and Rogue Venom, Customer Service—that’s Nocando and Joe Sue and Kail. We were part of that generation, and half of us became this group called Customer Service and another half of us became this group called Swim Team—that was me, Dumbfoundead, and Psychosiz. Psychosiz was in Customer Service as well.

Yousef: How did being a battle-rapper influence your music? I know the battle-rap scene in LA is far more aggressive and grittier than your music is now.

Open Mike: Yeah, but when I think about me growing up in Chicago and starting to rhyme then, the people that I rhymed with then, there was a lot of battling in that. I cut my teeth in one-on-one, freestyle battles, so I still have that in me, I even did a little bit of the battling in the battle-scene now, but when it comes to the kind of music that I want to make, it’s just not quite that aggressive for the most part. I come from that, and that is definitely in me.

Yousef: Are there any distinct challenges that you’ve faced, being an independent artist, that you believe drastically shifted the trajectory of your career?

Open Mike: I think part of it is just understanding that you’re not always going to have the same amount of resources as people who are at the top of the game. For me, I come from the Project Blowed, and another thing that Project Blowed taught me aside from style was the business of how to have a career when you aren’t signed to a major label. I learned a lot about how to do things DIY – how to book your own tours, how to do your own press, how to get your own albums pressed up. I don’t necessarily do all of that now, but I think having that spirit of knowing how and taking responsibility for making your own career and not waiting for other people is something that you have to lean on when you’re indie, and something that you need to operate in the mindset of. You know when you come out with an album, you’re not going to have $250,000 to make videos with. You might have $5,000, you might have $7,000, you have to be more creative with how you get the most out of that and try to figure out how to make a splash with less.

Yousef: Going off of that, what was it like starting your own label, AutoReverse?

Open Mike: It’s been challenging, but I think it’s an important thing to do. That’s part of the indie thing too—it’s on people who have achieved any measure of success, as hard as it is to do so in this, to help make a space for the younger ones that come along. That’s part of the reason of why to have a label. A lot of the labels that I’ve been on were set up for that same reason: so that people coming up had a platform to put releases out through, because that’s not always been the case, and it’s usually on artists that have achieved something to be able to make that happen, going forward.

Yousef: What inspired you to start your Comedy Central show [The New Negroes]?

Open Mike: I don’t think that’s as much of an inspiration thing as much as it was just an opportunity thing that came about, because I have spent a lot of time and energy in the comedy scene out here and have a lot of relationships there. That show wasn’t my idea, it was my co-host’s idea and I was just fortunate enough to be able to be along for the ride and be able to learn a little bit about how that world works.

Yousef: When you’re developing content for television though, how does your creative process differ from when you’re making music?

Open Mike: It’s a lot more collaborative. A lot of the music choices that I make, I don’t have to answer to anybody, I don’t have to run it by anybody; it’s me in the studio. I might get beats from other people, and eventually I take the stuff to other people to get it mixed and mastered, get additional instruments, get vocal collaborations, but it’s a lot of me making the decisions. In the TV world, there are people involved at literally every step of the way. There’s a lot you can do in terms of concept and writing on your own, but it’s a higher stakes world, and that means that a lot of people have a voice in what does and doesn’t happen at every step of the way.

Yousef: What motivated you to start your own wizardry talk show, LIVE FROM WZRD, back in 2019?

Open Mike: Again, that was another opportunity that happened to open up for me, and I just wanted to take advantage of it. That show, I wasn’t a creator of or anything like that, I just got approached to act in it and be a host of it. Again, it’s just being in the right place at the right time, and having an opportunity open up.

Yousef: In “Thirsty Ego Raps” on Dark Comedy, why do you call yourself Lord Bravery?

Open Mike: That came from this old cartoon called, “Freakazoid!” In the ‘90s, there was this character that I think was called Freakazoid, and there was a character called Lord Bravery and that had always stuck with me. When it comes to me writing songs like that, a lot of it is just pulling random references from my head. The reason it’s in the song is because it was in my head, basically.

Yousef: Being one of the architects of the sound & the artist to coin the term, “Art Rap,” how do you feel about the direction that the genre is going towards?

Open Mike: I’m not sure I know what direction it’s going towards, but the thing about a genre like that is, it’s always going to change and develop and the people who want to wave that flag, you can be pretty confident that they’re going to be doing stuff that pushes the sound forward; they’re going to be doing stuff in unique ways, and that’s really what defines it anyway. I don’t think the sound was ever uniform. It’s always been about opening the boundaries of it and giving people this space to feel like they can make whatever weird and unique decisions that they want to make in it. As long as it’s still moving that way, I feel like it’s doing what it’s supposed to.

Yousef: What was your emotional state when you worked on Anime, Trauma and Divorce? I can imagine that it served as a very therapeutic experience for you.

Open Mike: Yeah, and because of that, my emotional state was all over the place. That’s why there’s a lot of different tones in the album, in terms of how songs feel, how some are humorous, some are dark, some are more triumphant, some are more defeated; all of that reflects all of the different mindsets I was in when I was writing the songs.

Yousef: Even on “The Edge of New Clothes,” the hook is incredibly dark and detached and fatalistic, the way you say you’re “Lying on the edge of a cliff/Watching everything fall down.” Why was this the first song that you wrote for the album?

Open Mike: It was the first song that I wrote because when I started writing, that was the first beat that I had that I really liked and wanted to do something to, and that just happened to be the mindset that I was in when I started writing for that song. That was far before I even knew what the album looked like, but it was a peak to myself of where things were headed.

Yousef: Did you find the music getting happier as you progressed, or was it still all over the place while you were recording?

Open Mike: It’s all over the place. The last song that I wrote was “Death Parade,” which isn’t a happy song, by any means. I had written some happier songs before that, but “Death Parade” being a song that’s really rooted in trauma, but not in a way where it hasn’t triumphed over it, it’s kind of sitting with it and trying to understand it.

Yousef: Back in 2018 you performed on the JoCo Cruise yourself, and you feature your live performance on that cruise as the outro track to Anime, Trauma and Divorce. What was that experience like for you?

Open Mike: Terrifying. The experience from where the song came from was absolutely terrifying, but it’s always stuck with me because we were able to turn it into a song the next day. To me, there’s something in spinning a traumatic experience into that sort of thing that really encapsulates the spirit of the album for me.

Yousef: Your music has a certain duality to it, where it’s both thematically dense with humor, as well as it’s very telling of personal stories of heartbreak and trauma. That being said, do you consider your life to be a tragedy or a comedy?

Open Mike: I think it is a healthy amount of both. I think, really looking at it objectively, there’s some triumph and there’s some tragedy; there’s a lot of laughs, but I’m also looking for a lot of laughs, and that’s why I can find them. It’s a heck of a story, man. I think it remains to be seen what genre the story ends up being.

Yousef: Being 40 years old in the game, and still consistently putting out music that resonates with fans of all ages, what are you looking to achieve in the next 5 years?

Open Mike: That’s a challenge that I’m looking in the face right now. I don’t know if I still want to be in the position where I’m trying to do that when I’m 45—then, I’m closer to continuing to do that when I’m 50, which feels really weird. I don’t know. That gets into the previous question too; a lot of that remains to be seen. I know I’ll always make stuff. I’m not certain if I’m always going to have the energy it takes to make room for myself in hip-hop when hip-hop has always been an arena for young people.

Yousef: It probably just depends on whether something comes to you and you’re like, “Oh, I need to put some type of body of work together to get this off my chest.”

Open Mike: Sure, but maybe the next body of work isn’t music. Maybe the next body of work is a 1-hour drama on TNT, who knows?

Yousef: After listening to Anime, Trauma and Divorce, what are you looking for people to know about Open Mike Eagle?

Open Mike: That I go through dark stuff, because you might not know that if you only listen to my music or see me on Comedy Central or whatever. I’m trying to make a space for myself to express darkness, and I think that’s what I wanted people to come away with. It ain’t all fun and games.

Interview conducted by KCSB’s Internal Music Director Yousef Srour.