An Interview With Tim Owens

As a part of various endeavors to grow KCSB’s archival collection, Archives Coordinator Lekha Sapers will be blogging about our collection of audio archives. For the remainder of the school year, you’ll get a chance to explore our collection, highlighting the stories of some of our most formidable alumni.

Mr. Tim Owens is a man of many hats. Among the most notable (during his collegiate career) are: service as KCSB’s Program Director, and service as the station’s General Manager two years later. The resume does not stop there, however. Owens is the sole producer of Where The Bank Burned, a radio documentary surrounding Isla Vista’s 1970 burning of the Bank of America. And I took the opportunity to chat with him, getting a firsthand look at those few eventful days on Embarcadero. As a continuation of my previous essay, he elaborates on his radio career, the Joel Honey Hearings, the bank burning, and the nearly-unknown IV 2 and IV 3 riots.

Both the interview audio and the transcript can be found below.

____________________________________________________________________________

Tim Owens: My name is Tim Owens and KCSB used to be my home during college.

Lekha Sapers: So what years were you active, Tim? At KCSB?

Tim Owens: I came to UCSB in 1967, and I started immediately working at the station in the fall of 1967. I did a morning show during that first year. The second year I was made the program director. In the fourth year, I was the General Manager.

Lekha Sapers: So what was the name of your show on KCSB?

Tim Owens: I don’t remember, frankly.

Lekha Sapers: Oh, really?

Tim Owens: Yeah. I honestly don’t remember.

Lekha Sapers: What kind of music?

Tim Owens: I was doing rock and roll.

Lekha Sapers: That’s interesting.

Tim Owens: Well, back then we called it rock and roll, but it was more of this new FM wave from San Francisco and England and all of that that was coming into play.

Lekha Sapers: So what is the new FM wave ? What was that?

Tim Owens: Well, FM radio went through a transition in the late fifties, first of all, it became more popular, but the presentation became a lot lower key as DJs started to smoke a lot of grass and go on the air and then play music by the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, Dylan, Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

Lekha Sapers: And from what I know, that kind of music was prohibited on KCSB, is that true?

Tim Owens: No, no, no. Only certain things like the Fugs. That group was prohibited and there were a couple of other ones that were prohibited. But, during the all night shows, people would play those records anyway.

Lekha Sapers: Yeah. The same thing goes on now when after 10:00 PM everyone’s saying we can play whatever we want.

Tim Owens: Yeah. Well, the laws are a lot looser now than they were back then because people were… one complaint and you have a complaint against the licensee. Which in this case would be the Regents of the university, so you don’t wanna mess with the Regents.

Lekha Sapers: How did that licensing work out? How did you get that set up?

Tim Owens: Yeah, when I arrived the station went on the air, in the Navajo dorm. And, but from what I understand, the Regents agreed to license an FM signal, or to apply for an FM signal from the FCC. And that was granted. And I believe the first transmitter was like 10 watts on campus, so it couldn’t go very far. In fact, it didn’t even get into Isla Vista or barely got into Isla Vista, but the intent was to cover the campus.

Lekha Sapers: So who was listening?

Tim Owens: You know, it’s a good question of who was listening, but eventually we knew that a lot were listening during the Isla Vista riots.

Lekha Sapers: The first one was in ’69, correct? That was the very first riot?

Tim Owens: There was a disturbance in 1969 and the African American students wanted to have an African American studies program. And so they, I believe it was early spring, maybe 69, they took over North Hall. And they barricaded themselves in North Hall until the university would agree to do a Black Studies program. And they did. It didn’t take ’em long to say, yes, we’ll do a Black Studies program , in which case they vacated the North Hall. But you have to remember that during that period of time there were various free speech activities all across the country, led in part by the University of California, Berkeley.

Lekha Sapers: Mm-hmm.

Tim Owens: Which just promulgated all this other stuff that came after. And in tandem with that you had the Vietnam War going on, and people like myself were getting drafted right and left to go fight a war that nobody wanted to fight. And so you had this resistance occurring on multiple levels: of race level, and the war level and just various others, rebelling against structure and establishment and society itself.

Lekha Sapers: So do you think that the rebelling that occurred both at the burning of the bank and the Black Student Union lock in, was that a direct result of Sister Campus UC Berkeley’s free speech movement, or was it treatment from police and authority and anti-establishment, anti-Vietnam stuff.

Tim Owens: You know, I really don’t know. I was almost a bystander to what occurred at the North Hall. I just know, knew that it was going on and I know just a little bit of the history of it. And I’m trying to put a couple of things in perspective. There was, and I think this was dealing with the Bill Allen situation, which came later. The university fired a professor by the name of Bill Allen for various reasons. And students got really angry and they went after the ROTC, which was a heavy component on campus here. And I think they broke windows at the R O T C building, but it was a disturbance on campus that required the campus police to intercede.

But I think that was post North Hall. I think North Hall was the very first incident.

Lekha Sapers: I would love to know why students were so attached to Bill Allen. Of course, he was a great professor as far as I know. But was it political?

Tim Owens: I think the politics, his liberal leanings for sure, and the fact that he was giving everybody a’s and they didn’t have to take tests, and all of that. I think all of that went into the decision that he was not a great professor even though students loved him. So let’s fire him, because there’s accreditation issues with respect to this as well.

Lekha Sapers: But I still have trouble seeing why the university would want to fire him. If Bill Allen falls into the vein of the anti-establishment rhetoric that the students were so heavily expressing , why was that the decision made on behalf of the university?

Tim Owens: Good question. And Chancellor Cheadle is no longer around for you to ask him, so… and I’m not sure who is around from that era that is still alive who could answer that question. But it was definitely some decision at the upper end, and it was on this campus that the decision was made, not at the Regents level.Again, you just had a wave of disturbances that were beginning to occur. And then when William Kuntsler came to Santa Barbara to do a speech, I believe in January of 1970, that’s when, that’s what triggered the first Isla Vista riot.

Lekha Sapers: Why was that so incendiary?

Tim Owens: Well, he was dealing with the Chicago seven as one of the attorneys. And he was pretty angry about what was going on with respect to the Chicago seven. And so he was invited to speak and he spoke out at Campus Stadium. And part of his speech, which is included in my radio documentary on the burning of the Bank of America, he’s encouraging people that if you’re not being listened to, to go to the streets and show them in the streets what you’re capable of doing. And so literally that night, some people went into the streets and started throwing rocks at a police car after they arrested a black man. And that kind of triggered things. I don’t know if it was the same night, I think it was the next night, where you had a larger throng of people out in front of the Bank of America, and some of them started to throw incendiary devices into the bank. And. that led to the whole bank burning.

Lekha Sapers: Were you around at the time of the bank burning? You mentioned that you were a UCSB student at that time.

Tim Owens: Yeah, I was. I lived half a block away from the bank. I was at the corner of, what’s the one that goes into from campus?

Pardall?

Lekha Sapers: Pardall. Yep.

Tim Owens: Pardall to Embarcadero. One of the two Embarcaderos, the closest one, I think Embarcadero Del Norte. There’s an apartment complex there at that northeastern corner that was three or four stories high. And I had a balcony room on the corner overlooking the bank.

Lekha Sapers: Did you see everything that went down that night?

Tim Owens: Pretty much. I got out on the streets too.

Lekha Sapers: Oh wow.

Tim Owens: I was curious to know what was going on, and Cy Godfrey was filing the reports. And he was the general manager, so I was available to help him and file the reports as well but he was doing a pretty good job. I don’t know what happened specifically with regard to the burning of the Bank of America. I’ve heard that they tried to light the curtains on fire first and they couldn’t get it to burn.

And so they started to light a dumpster on fire and a couple people tried to roll the dumpster through the door, which they were capable of doing, and that’s what started the big fire that ultimately burned the bank to the ground. And the only thing that was really standing was a little bit of the foundation, the foundational walls. And the safe, which had melted. It’s literally deformed, it looked like somebody took a big metal safe and twisted it. And that’s, and that gives you an idea how hot that fire was. And we watched it burn. After the fire was going, they tried to send the fire trucks in and people were stoning the fire trucks.

And they were concerned for their safety. And the cop cars were chased out and all we did was watch the bank burn after that because no cops, and roasted marshmallows. But, until about two in the morning we said, well, this is just gonna keep burning until it burns to the ground, so let’s go home.

Lekha Sapers: So why the bank, why not the local taco bell?

Tim Owens: It’s a symbol of establishment, Bank of America. The biggest bank in the country at the time. Let’s send a message.

Lekha Sapers: Do you think that the burning of the bank got the student’s point across? It is extensive in UCSB lore even today, but do you think that it was enough?

Tim Owens: I think it got a point across. Again, all of this was just a chain of events going on across the country, so it was just one of those drastic actions that had surfaced in the press across the country. And that’s one thing they remember about that time was the ‘Oh, that’s the place where the bank burned’.

Lekha Sapers: I’ve read articles in the New York Times about both the Bank Burning and the Joel honey hearing, so it’s crazy that those things have reached that extent.

Tim Owens: And it’s interesting, I made the decision to broadcast the Joel Honey hearings, and I was the anchor for those hearings.

Lekha Sapers: Wow. So how did you find the information about Joel Honey and those abuses?

Tim Owens: Well, I didn’t have to do anything. I was just covering the proceedings with where everybody else found out the information. And during that hearing, we’re jumping ahead from the riots. This was now past my management, but I was hired back as a consultant by the station, and so I said, we gotta broadcast the Joel Honey hearings.

Not only that, but by now we had moved the transmitter up to Broadcast Peak so all of Santa Barbara could hear it. This is how it got on the map. With the Joel honey hearings, which, for those who are a little bit older in the audience, this was like an OJ Simpson hearing at the time.

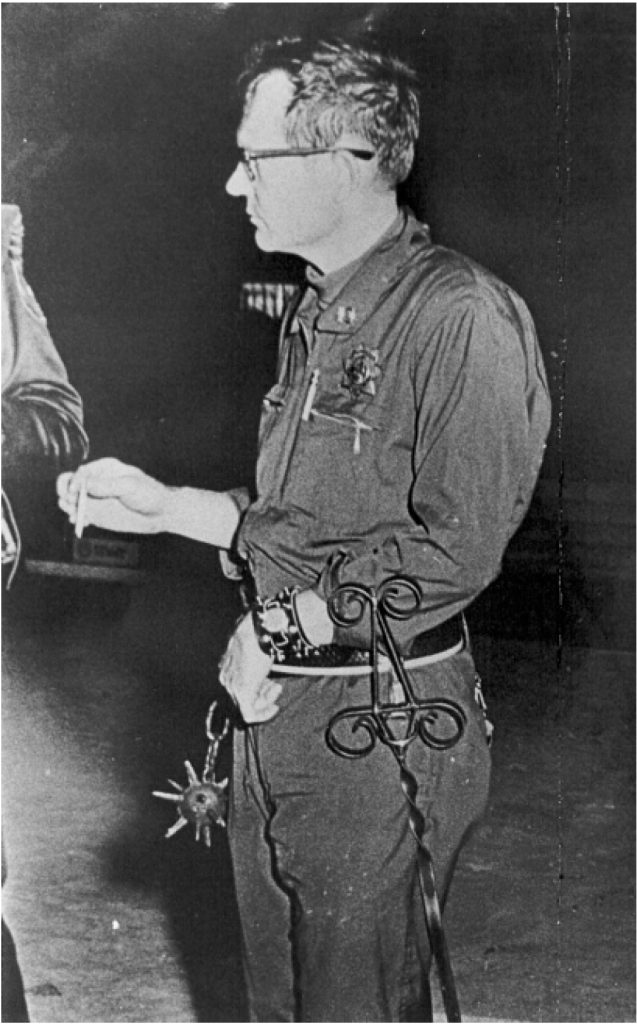

Because everybody was just glued to these hearings day in and day out because you had this incredible testimony going on, not only from the standpoint of how the police were beating people and indiscriminately, but also from the standpoint that Captain Joel Honey himself was an instigator to beat these people and wielding in what was called Perfect park, then, wielding a Spanish sword and a ball and chain he was carrying on himself and, and leading a charge by the sheriffs.

Lekha Sapers: I saw that picture with the ball and chain and the sword.

Tim Owens: Mm-hmm.

Lekha Sapers: That’s absolutely absurd.

Tim Owens: It’s an iconic picture for this area.

Lekha Sapers: What kind of power trip was this guy on?

Tim Owens: Well, he didn’t testify on his own behalf, so we don’t know what kind of, what was going on with him psychologically. But you give people power. A lot of people, as we well know, abuse that power. I mean, we see it in government every day. It happens all the time. It’s the old saying: ultimate power corrupts ultimately.

So the Joel Honey hearings were great. All I had to do was set it up and when they took a break, I had to fill it and send it back to the station. And they filled with music and then we, they came to me and I said, okay, it’s starting now. And so they came to me and reset it up again and said, they’ve talked about this, this, and that.

And, I had to run the wires every day myself. And the little mixer box. And, because I got a feed from the audio system inside, I had to sit outside the doors so I would see everybody coming in.

Lekha Sapers: I see. So why did you decide to document the hearings themselves?

Tim Owens: It’s just me and my radio sense, I guess. I thought that this is important for the community to hear. So if we’ve got the opportunity to do it, and they, and I inquired and they say, yeah, you can broadcast these. These are public hearings, why not?

Lekha Sapers: Where were they held?

Tim Owens: They were held at the county board of supervisor’s office.

Lekha Sapers: So you just brought all of your gear down to the county board of supervisors and set up shop?

Tim Owens: Yeah.

Lekha Sapers: Wow. That’s very impressive.

Tim Owens: Yeah, it was. It was very exciting and you had all this lead up to it. You had the burning of the Bank of America which, in a way by three in the morning, two in the morning.

It was just so solemn. Everybody was like, okay, well now what? I guess we’re in serious trouble. And so the next day, next evening, people were gathering in the streets again, and the sheriffs were lined up on campus across Pardall and they started landing, you know, hurling in grenades.

Rocket launched grenades of tear gas to break us up. And, because they didn’t want to come at us. They started to, but they were basically forced to retreat because there was a lot of rock throwing going on. There were people who had bandanas over their face and they had trash can lids so that when a grenade was launched, they would knock it down with the trash can lid and another person had a bucket of water and doused the grenade in the bucket of water.

So it was somewhat organized. I mean I was on the street for a minute and I said I can’t stand the tear gas. It’s just like too much. So I got up into my apartment and was watching a lot of this go, go on for my apartment balcony. because I was right there at Pardall. And then the tear gas just got to be way too much for all of us.

But at that point the sheriff said, ‘this isn’t working.’ They retreated, they left the campus. And again, everybody had nothing else to do, so they went home. Next thing we know is that by five in the morning, the National Guard was rolling in. The governor at the time was Ronald Reagan, and he said if they want a blood bath, we’ll give them a blood bath.

Lekha Sapers: What was the relationship between students and then Governor Ronald Reagan?

Tim Owens: Hated him.

Lekha Sapers: Yeah, of course. I can imagine. And did they have the same relationship with Cheadle as well?

Tim Owens: Actually, Chancellor Cheadle was a pretty good guy. And I don’t think that he was hated. No, not at all. I think he was a symbol of the establishment. So in that sense, he was, you know, part of the establishment. So in the larger sense, yes, maybe. But personally he was a good guy.

Lekha Sapers: Was there any disciplinary actions enforced on behalf of the school by Cheadle or was it mostly just extreme law enforcement?

Tim Owens: No, they were letting law enforcement on campus and then the law enforcement, once the National Guard rolled in, that night, so this would be the third night, um, the National Guard was going around in these dump trucks with guns pointed at you. I got out on the balcony and, first of all, on the back of the truck, and I think this is documented in the documentary that I did, it said Pig Patrol. And they had printed that themselves, the National Guard. There was either in the National Guard or the sheriffs, they may have been sharing duties, but I remember The National Guard, or maybe it was a sheriff, pointing a shotgun at me and I just hit the deck, literally hit the deck and I believe the trigger was pulled.

Lekha Sapers: Oh my God.

Tim Owens: Yeah. But it hit the tree next to me. I had a tree next to me. I heard this scattering and pellets and what have you. But they were shooting over people’s heads. And they were going into apartments and mainly busting people on the street, the ones that they could find. And then, let’s see, I think at that point that was it for that riot. And then, everybody went back to their studies and things dissipated. The Bank of America rolled in a quanta hut and set up a temporary bank to resume operations. Took ’em about a month to do that, if I recall.

Lekha Sapers: Why did things just return to business as usual? Was it just police forces left there?

Tim Owens: There wasn’t a triggering event.

Lekha Sapers: So then what triggered the subsequent riots?

Tim Owens: The second riot, I’m not exactly sure what triggered it. But what I do remember is again, the bank became the symbol of the rallying point, and some people were trying to, again, burn it down. And in this case it would’ve been a lot easier because it was just a makeshift trailer. One student in particular, Kevin Moran, stood on the bank doorsteps. And then as that was going back and forth, all of a sudden you had this flotilla of sheriff’s cars coming in and they were just shooting up in the air and waving, and one one officer shot and killed Kevin Moran.

Lekha Sapers: Was it true that he was trying to defend the bank?

Tim Owens: Yeah.

Lekha Sapers: That’s interesting. Was the crowd very divided at that point in intention?

Tim Owens: Yes, it was.

Lekha Sapers: Why was that?

Tim Owens: Well, I think he wanted some people who did not want to go down this route and figured that it was pointless. And, it’s not going to achieve anything. And then there were others who said, this is the only way in which we can be heard. So you had those two opposing factions going against one another. The next day, sheriff James Webster basically had to explain why this kid was killed. And he said, well, a rifle accidentally discharged.

Yeah. Bull.

The rifle did not accidentally discharge. And Kevin Moran was shot intentionally.

Lekha Sapers: Can you talk about the student reaction after everyone found out about his death and that the police shot and killed him?

Tim Owens: Well, we were blown away. It sort of quelled us on that one. I can’t remember too much after that, whether there was another night of disturbance or two or whatever, but the National Guard got back in again. And then things calmed down. And then in June, early June, it kicked up again with the third riot. This time James Webster, the sheriff, said we’re gonna bring in the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, who have been known to be bruisers, racists and thugs essentially. And they were. They came in and I think by the third day people, 600 or so people had gathered in Perfect Park. And, they were sitting down and they were warned to leave. And again, this audio is captured in my documentary. They were warned to leave. They didn’t, and a charge was led and they just started indiscriminately beating people and dragging them off. And then they just started patrolling the streets and people would come out and then run back to their apartments.

They’d break down the doors of the apartment and arrest people and pull ’em out of their apartment. And in my documentary, I have a scene of a guy, of a group of kids who had the recorder going. During the break in and he was able to hide the recording, I mean his recording device as everything was going to hell there, as they were being beaten and dragged off. And then once you hear the door break open, you hear the sheriffs come in and then you hear all this screaming going on by the women who were there and a couple guys getting their heads scrunched and then silence. After they leave, there’s just room noise and one sheriff says, something to the effect:

he goes, ‘Oh my God, what are we doing’?

There were a lot of arrests. There was anger on both sides. There were those who were pro-establishment, what we called pro-establishment, Pro-War, Sheriff’s Department, symbol of authority. And on the other: this isn’t right. We need to be protesting and so it was a very polarizing time. And if you think today is polarized, it may be more so politically, but back then it was more physical.

Lekha Sapers: And I understand the establishment and anti-establishment dichotomy, but were there people in Isla Vista just protesting just to protest, just to get a reaction out of the police?

Tim Owens: Sure. There are followers and there are leaders. Some people are curious too. So they found themselves in the street. Some people were throwing rocks.

Lekha Sapers: So would you say that the majority of people were protesting because of frustrations with authority or because they just wanted to be there to be a part of it?

Tim Owens: I think the latter. I think that protests are generally always led by a small faction of people. And then you have people who are curious and you have followers. And those are the people who often get hurt. But they’re, I would say probably the bulk of the Isla Vista population was indoors. They didn’t want to get involved, but the ones that were, were curious and wanted to go out even though they may not have had an ax to grind, they just wanted to go out and support the others. It’s the riot mentality, I think, that once you get what happened on Capitol Hill on January 6th, it’s the same thing.

Lekha Sapers: Mm-hmm.

Tim Owens: People just get into the flow of it and suddenly they find themselves doing things that they shouldn’t be doing.

Lekha Sapers: Would you say that these were started by a small group of people because of the sheer spectacle of it?

Tim Owens: Yeah, absolutely.

Lekha Sapers: Wow. So how much of the two, the April riots and the June riots, were you present for in person?

Tim Owens: All of them

Lekha Sapers: On the streets?

Tim Owens: Yeah. My role was to file periodic reports. So I was trying to take the standpoint of an objective journalist. To say: ‘here is what’s going on.’ If you listen to the recordings, the KCSB journalists, the reporters– and we’re all students, were doing a great job.

Lekha Sapers: Mm-hmm.

Tim Owens: Growing up very quickly. When your heart may be into being one of the rioters, you didn’t do it. I didn’t know any of the people at KCS B who participated in that way.

Lekha Sapers: And it must have been difficult to give objective reports when you see this, these police, these pigs that are just beating up on people.

Tim Owens: Yeah. There were a couple of reporters who broke down and seeing all of this going on certainly sounded emotional when they were giving their report.

I think that my documentary captures a lot of that emotion that was going on by those reporters, particularly during the head busting at Perfect Park in the third riot.

Lekha Sapers: Did it ever get to that point for you when you were reporting?

Tim Owens: I didn’t feel terribly emotional about it, frankly. I was also not out on the street for the third one. I did not want to get in trouble.

Lekha Sapers: Coming out of your senior year as GM, and then all of a sudden just graduating in June, was there a legacy that you wanted to leave after leaving UCSB and KCSB?

Tim Owens: Well my, my legacy at KCSB was just to shepherd it along… provide the management needed for students to come in and have a good time on the radio, learn about news production, learn about public affairs production, learn about being a DJ in music production, or production in general. Opportunities for people to be a promotion director, you know, whatever. There were about 60 people that I was managing. And then getting the, making sure that the final aspect of getting the transmitter up on Broadcast Peak was in place. So that was my other task.

The other thing: we occasionally would do remotes from Perfect Park. So we did quite a few remotes too. I was pretty much open to helping those who wanted to. Facilitate their ability to do it. And for me it was just a, I had an interest in broadcasting. This was a natural extension of hanging out at a radio station in my own town of Thousand Oaks, where I used to just watch these DJs spin records at age 13 and age 14, age 15, and then they put me on the air at age 16. And then, eventually before I came up here, I was working the midday shift at the radio station. So this was just an extension of my broadcast interest, which continued after. because I was discovered by National Public Radio and immediately started filing reports for National Public Radio.

Lekha Sapers: So what did you do there at NPR?

Tim Owens: I was a news reporter. I was working primarily out of Santa Barbara for the first year and then they, I was invited to come up to San Francisco where they had the West Coast Bureau. And so I started filing reports out of there, all freelancing. Living by the skin of my teeth most of the time, waiting for the check to come in, which eventually led to a full-time position with NPR. They asked me in 1976. Somebody I’d been working with on the cultural programming side said, ‘yeah, I know you know a lot about jazz. Do you have any ideas for doing a jazz series’? I said, yeah, I’m gonna go around the world recording jazz concerts and making radio shows. And he said, ‘oh. Oh, okay.’ Well, the idea got funded six months later, and so off to DC I went to start up my very first NPR show called Jazz Alive, a series that lasted about six years on NPR before NPR had a fiscal crisis in 1983, and literally laid off half the staff. Despite the fact that I had the third most successful show on the air, they laid us off and that was that.

Lekha Sapers: That’s such a bummer because that is the coolest job ever.

Tim Owens: Yeah. because I ended up going to work for Voice of America and that was an experience in and of itself because the Voice of America, the long and the short of it is, this is the broadcast that goes behind the Iron Curtain or what used to be the Iron Curtain in Eastern Europe and throughout the world. But the thing that it’s important to remember is that when they report news, a Voice of America, which is the wing of the government, it’s what’s left out. It’s sort of like Fox News. Fox News does some reporting. Most of it is opinion, but it’s the news that they leave out. And that’s the questionable news, the kind of news that may spring a thought into your head: well, wait a minute. So that’s what the USIA was doing at the time.

And then I landed a job as the director of programming for WETA radio in Washington, DC which was a classical music NPR station at the time. And that lasted nine years. And I became the original founding member of the Public Radio Program Directors Association and all of that. WETA for those who may not know, they do the news Hour, on PBS.

They’re a PBS station as well. So I did that for nine years and then NPR came back to me: we’d like to do some more jazz. We have this, these grants to do jazz. Do you think you can come up with some ideas? And I say, yeah, I’d like to do a documentary series on the history of jazz, but I want to, I wanna do artists that are alive so they can talk about themselves for the most part.

And so I got a host by the name of Nancy Wilson, the singer, and we did jazz profiles. We made 350 some odd one hour radio shows.

Lekha Sapers: Wow. How long did you do that for?

Tim Owens: That was from 1995 to 2002.

Lekha Sapers: And then post 2002?

Tim Owens: NPR went through a financial crisis in 2002 and said, we’re getting rid of the entire cultural programming department. Two weeks earlier, I had won a Peabody Award for Jazz Profiles.

Lekha Sapers: That’s incredible– congratulations.

Tim Owens: Well, that was my second one. Jazz Live also won a Peabody Award. And then, the cultural programming department of NPR was awarded the Presidential Medal of the Arts.

So we went to a ceremony at the White House. There were about 50 of us, and still, the crazy guys at NPR say: ‘I just wanna get rid of cultural programming. We’re a news organization.’

Lekha Sapers: Where’s the soul then? Where’s the soul at that point?

Tim Owens: Well, that’s what we were asking, too. And there was a lot of pushback for that very reason. But wait a minute, isn’t it the mission of NPR to be diverse? But it didn’t do any good. So, we stopped production of jazz profiles after 350 shows.

Lekha Sapers: So before I close out the interview, I would love to ask you about the process of moving the transmitter to Broadcast Peak.

Tim Owens: Sure.

Lekha Sapers: What went into doing that? Was it a strenuous process?

Tim Owens: It was a multi-year process. And it really does date back to the chief engineer JD Stroller, uh, John David Stroller and Mike Bloom. And before Mike Bloom, I think Rick Kendall may have had something to do with it. Either Rick Kendall or Tom Adams. And they dreamed: this is just a campus radio station, what if we could expand the signal. So they started looking into it and JD Stroller came up with a plan based on what the FCC would allow in terms of an antenna contour and a power, whatever the power was. And so with that, they worked on filing the application with Chancellor Cheadle and the Regents okaying it through basically Chancellor Cheadle. It was a long process. The application at the end of Cy Godfrey’s tenure as General Manager, the year before me, was approved. So when I came into the General Manager-ship of KCSB in 1970-71, I implemented it, because now we were ready to go. It was pretty simple at that point. It’s just being in the right place at the right time. JD Stroller took the four hour trip to go up to Broadcast Peak.

And because you had to access it by Jeep, he was up there and we were on top of Storke Tower, Steve Selman and myself pointing the microwave antenna towards Broadcast Peak to get the strongest signal from the station to the broadcast peak. And there were no rails up there. We were on top of the roof at night doing this.

And I threw the switch.

Lekha Sapers: That’s some really cool stuff. And that’s the difference between interviews and written accounts. You don’t get a lot of the nitty gritty from textbooks that try to detail KCSB’s history.

Tim Owens: Yeah. There’s a lot of history there and I guess you have to be a KCSB-ite in order to understand it. Or at least appreciate it.

Lekha Sapers: Well of course that’s what we’re trying to do here is make everyone into a KCSB-ite. Tim, thank you so much for coming.